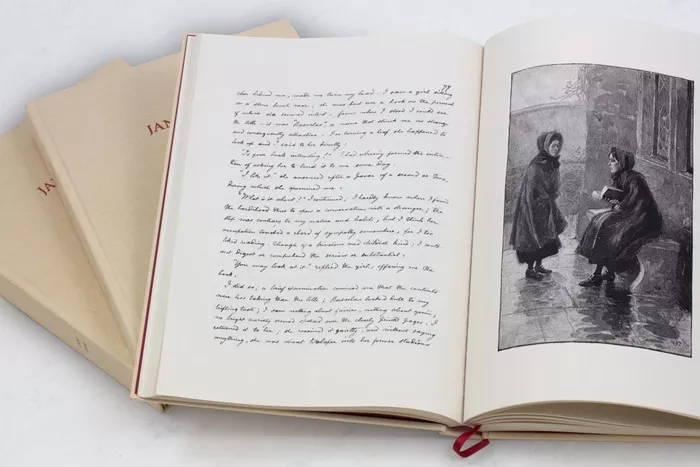

In Jane Eyre, Charlotte Brontë introduces readers to a protagonist whose unwavering passion, integrity, and determination have ensured her place as one of literature’s most enduring heroines. Since its publication in 1847, the novel has captivated generations of readers, not just for its vivid storytelling but for its portrayal of Jane’s indomitable spirit, which continues to resonate today.

A character of strength and resilience, Jane Eyre rises above her humble beginnings—marked by orphanhood, mistreatment, and deprivation—to assert her right to happiness. Even those unfamiliar with the book are likely aware of its iconic themes, including the governess and the madwoman, which Jane Eyre helped define in the Victorian era.

A Novel of Firsts

Brontë’s novel, subtitled An Autobiography, offers an intimate glimpse into the world of its young heroine. Like many aspects of Jane Eyre, the novel’s narrative and themes are deeply influenced by Brontë’s own challenging life experiences. Born in Yorkshire, Charlotte Brontë endured early personal losses, including the death of her mother and two older sisters. These formative tragedies shaped her view of the world and ultimately influenced her writing.

Charlotte’s life was one of struggle—she faced failure as a teacher and governess before finding success as a writer. Along with her sisters, she sought to make a career in literature, leading to the publication of three now-classic novels—Wuthering Heights, Jane Eyre, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall—that collectively marked the start of a remarkable literary movement in Northumberland.

Early Struggles and Triumphs

Jane Eyre opens with a powerful exploration of the orphaned Jane’s early life, marked by cruel treatment at the hands of her aunt and cousins. Though subjected to harsh abuse and neglect, Jane refuses to submit to the demeaning circumstances that surround her. Her rejection of meek obedience, embodied in her resistance to the Christian piety that defines the charity school she later attends, marks the beginning of her defiant journey toward self-reliance and inner strength.

The bleak conditions at Lowood School, where Jane endures hunger and mistreatment, are drawn from Charlotte Brontë’s own experiences with the harsh realities of boarding school life. Yet, even in such dark settings, Jane’s resilience shines through, as she forms a deep friendship with the pious Helen Burns, whose untimely death ultimately sets Jane on a path toward greater independence.

The Evolution of Jane’s Character

As Jane matures, so too does her sense of self. Her next role as governess at Thornfield Hall introduces her to Edward Rochester, a man whose emotional complexity and troubled past bring new challenges to Jane’s sense of self-worth. The unconventional courtship between Jane and Rochester, marked by power dynamics, social class differences, and moral dilemmas, forms one of the novel’s central conflicts.

Rochester’s emotional dependency and flirtations, including his use of deceptive tactics to gauge Jane’s affections, only strengthen Jane’s resolve to maintain her dignity and independence. Her refusal to submit to his demands, even when she is deeply in love, is a defining moment of the novel—highlighting her belief in the importance of personal integrity and equality in relationships.

Feminism, Race, and Colonialism

While Jane Eyre is often seen as a narrative about love and self-discovery, it is also a critique of Victorian society and its rigid structures. The character of Bertha Mason, Rochester’s first wife, who is confined to the attic in a gothic twist, has long been discussed in feminist criticism. In their landmark work The Madwoman in the Attic (1979), scholars Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar explore how Bertha represents the repressed aspects of female experience in a patriarchal society.

Jean Rhys’s 1966 novel Wide Sargasso Sea further complicates Bertha’s character, presenting her as a victim of colonialism and exploitation. Through this lens, Bertha becomes a symbol of the intersectionality of race, class, and gender oppression. As Brontë explores themes of power and submission, the novel implicitly critiques the colonial mindset that permeated the British Empire, especially as Jane encounters missionary St. John Rivers, whose cold ambition contrasts with Rochester’s passionate nature.

A Radical Resolution

The novel’s conclusion sees Jane returning to Rochester after his tragic fall from grace, where she assumes a caretaker role. In doing so, Jane redefines the traditional gender roles of the time, embracing both love and agency in a way that was groundbreaking for Victorian literature.

Jane’s declaration that “I am my husband’s life as fully as he is mine” encapsulates the radical equality at the heart of the novel. In choosing to marry Rochester—who has become dependent on her both physically and financially—Jane achieves a balance of power and affection that was rarely depicted in Victorian novels.

Brontë’s Jane Eyre continues to resonate as a story of self-empowerment, offering a compelling portrayal of a woman who refuses to sacrifice her dignity in the pursuit of love. Through Jane, Brontë presents a model of integrity, passion, and independence—values that remain just as relevant today as they were in the 19th century.